Why Most Self-Published Books Sell Under 250 Copies

The 250-copy statistic gets thrown around constantly in publishing discussions. It originates from various industry surveys, and while the exact number varies by source and methodology, the underlying reality remains consistent: most self-published books sell very few copies.

This isn’t a condemnation of self-publishing. Traditional publishing has its own sobering statistics—most traditionally published books don’t earn out their advances, and plenty sell fewer than 1,000 copies despite professional support. The difference is that traditional publishers absorb those losses across their portfolio. Self-published authors feel every unsold book personally.

Understanding why most books underperform is the first step toward ensuring yours doesn’t.

The Visibility Problem

Amazon lists over 12 million Kindle ebooks. New titles publish at a rate exceeding 2,000 per day. The fundamental challenge isn’t quality—it’s attention in an impossibly crowded marketplace.

Books don’t sell themselves. This seems obvious stated plainly, but author behavior suggests many people believe otherwise. The fantasy of writing something wonderful, uploading it, and watching sales materialize is exactly that—a fantasy. Even exceptional books require active effort to find their readers.

The visibility problem compounds over time. Amazon’s algorithms favor books that sell, surfacing them in recommendations and search results. Books that don’t sell slip into invisibility, making future sales even less likely. The rich get richer while struggling books struggle harder.

Breaking through requires either significant marketing investment, an existing platform with built-in audience, or both. Authors who approach self-publishing expecting the platform to do the work are setting themselves up for disappointment. The platform provides access to potential buyers. Converting potential into actual requires work the author must do.

Category Saturation and Competition

Some categories are more crowded than others. Romance, thrillers, and fantasy—genres with passionate, high-volume readers—attract proportionally more authors. The opportunity is larger, but so is the competition.

Succeeding in saturated categories requires either exceptional execution or finding underserved niches within the broader genre. A generic contemporary romance competes against thousands of similar titles from authors with established readerships and larger marketing budgets. A contemporary romance targeting a specific underserved audience faces less competition for that audience’s attention.

Niche selection involves tradeoffs. Smaller niches have fewer competitors but also fewer potential readers. The ideal position balances addressable market size against realistic competitive advantage. Too broad means drowning in competition; too narrow means the ceiling is too low to justify the effort.

Authors who succeed in competitive categories typically start in adjacent niches and expand. Building a readership in a manageable space, then carrying those readers into broader competition, works better than attacking the entire market from day one.

The Cover Problem

Readers judge books by covers. Eye-tracking studies, click-through data, and common sense all confirm this. A weak cover doesn’t get a chance to prove the writing inside is strong.

The cover problem manifests in two ways. The obvious failure is an unprofessional cover—amateur design, poor typography, low-quality images. Less obvious but equally damaging is the professionally designed cover that signals the wrong genre or tone. A romance novel with a thriller cover attracts the wrong readers and repels the right ones.

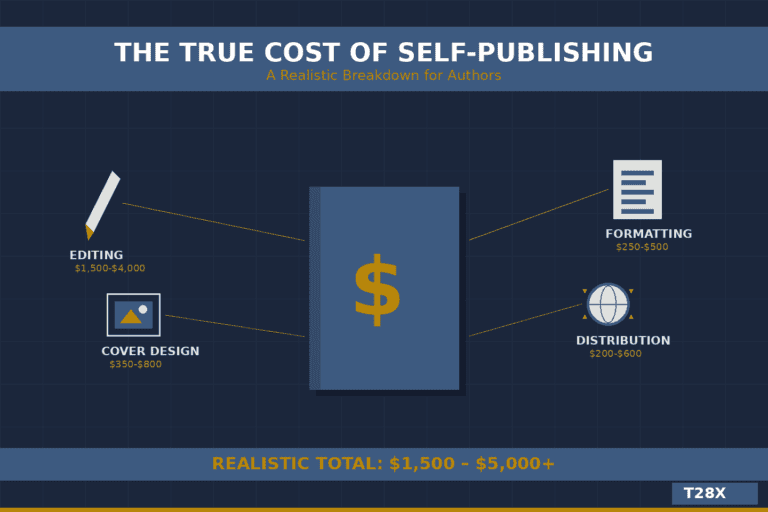

Cover investment correlates with sales outcomes more strongly than almost any other variable authors control. The correlation isn’t perfect—good covers don’t guarantee success—but bad covers reliably predict failure. Spending $100 to save money on design costs sales worth far more than the savings.

Genre research precedes cover design. Understanding what successful books in your category look like, what visual language readers expect, and what trends are emerging versus fading informs briefing designers effectively. Authors who skip this research get covers that might be attractive in abstract but fail to function as genre signals.

Description and Positioning Failures

After the cover earns a click, the book description determines whether browsing becomes buying. Most self-published book descriptions fail this test.

Common description problems include: leading with biography instead of hook, summarizing plot without creating desire, using generic language that could describe thousands of books, burying the compelling elements under setup, and running either too long or too short.

Effective descriptions sell emotion and stakes, not information. Readers don’t buy books because they understand the plot. They buy books because the description makes them feel something and want more of that feeling. The technical craft of description writing differs substantially from the craft of writing books themselves.

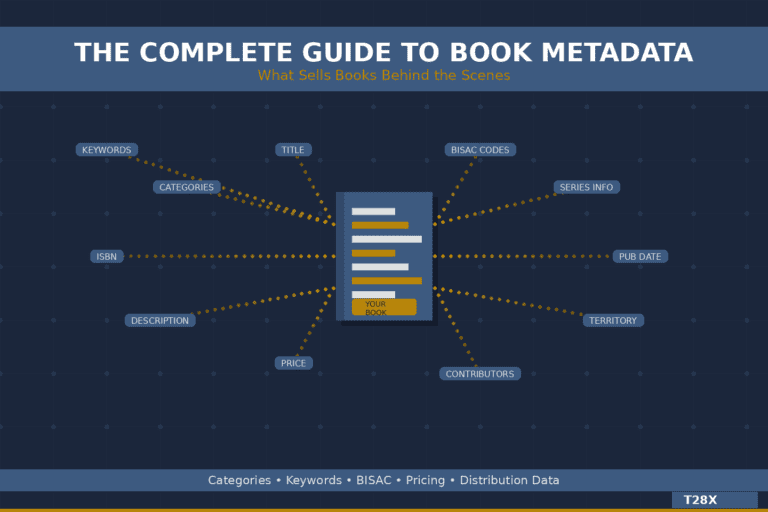

The product page as a whole—cover, description, categories, keywords, also-boughts—creates a cumulative impression. Weakness in any element undermines the others. A strong cover driving clicks to a weak description converts poorly. A strong description helping a weak cover still loses readers who never clicked at all.

Pricing Strategy Mistakes

Pricing self-published books involves counterintuitive dynamics. Too cheap signals low quality. Too expensive creates purchase friction. The optimal price depends on genre, length, series position, and marketing strategy.

New authors often underprice out of insecurity. A $0.99 price point might seem like removing friction, but it actually raises suspicion—why is this so cheap? Professional self-published books typically price between $2.99 and $6.99 for ebooks depending on genre and length, with higher prices for specialized nonfiction.

The $2.99 threshold matters because Amazon’s royalty structure changes there. Below $2.99, authors earn 35 percent royalty. At $2.99 and above, they earn 70 percent. A $0.99 book earns roughly $0.35 per sale. A $2.99 book earns roughly $2.09. The cheaper book needs to sell six times as many copies to generate equivalent revenue.

Strategic discounting works differently from permanent underpricing. Temporarily reducing price for promotions, using permafree first-in-series to drive readthrough, and running coordinated price pulses for visibility all represent legitimate tactics. Staying permanently cheap because you don’t believe your book deserves more is not a tactic—it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Series Abandonment Pattern

Self-published authors who succeed almost universally write series. Series build readership momentum, create multiple purchase opportunities per reader, and allow marketing investment to compound across titles. Standalone books can sell well but face structural disadvantages.

The problem is that many authors start series but don’t finish them. A first book launches, sells modestly, and the author either loses motivation or pivots to something new. The readers acquired by book one never get books two and three to buy. The investment in building that initial audience yields no return.

Series completion signals professionalism and reliability to both readers and algorithms. Readers hesitate to start series from unknown authors who might never finish them. Amazon’s recommendation systems favor authors with backlist depth. The virtuous cycle only engages when authors follow through.

Even if book one underperforms, finishing the series often makes more sense than abandoning it. The act of completion provides learning. The backlist exists for future marketing efforts. And occasionally, later books catch on and pull earlier books with them—something that can’t happen if those books don’t exist.

Marketing Timing Mistakes

Authors commonly treat marketing as something to figure out after the book is written. This sequencing virtually guarantees suboptimal results.

Effective book marketing starts during writing. Building audience, establishing platform presence, connecting with readers in your genre—all of this groundwork pays off at launch. An author who publishes their first book to an engaged mailing list of 500 interested readers faces completely different launch dynamics than an author publishing to silence.

Launch week matters more than any other period. Amazon’s algorithms heavily weight early sales velocity. A strong launch creates visibility that drives organic sales that reinforce visibility. A weak launch means struggling against algorithmic headwinds that only strengthen as the book ages.

Post-launch marketing can rescue underperforming books, but it requires substantially more effort and often more money than launch marketing. The author who “doesn’t want to think about marketing until the book is done” has chosen the hardest path without realizing it.

Quality Floors and Ceilings

Quality establishes a ceiling, not a floor. Excellent writing makes success possible but doesn’t guarantee it. Poor writing makes lasting success essentially impossible regardless of marketing effort.

The uncomfortable truth is that quality alone doesn’t sell books. Books with writing flaws but compelling hooks outsell technically superior books with weak premises. Readers care about their experience—was the book engaging, did they enjoy the time spent—more than objective craft measures.

This doesn’t mean quality doesn’t matter. It means quality operates as necessary but not sufficient. A book must clear minimum quality thresholds to sustain reader satisfaction and generate word-of-mouth. Beyond that threshold, other factors determine outcomes.

Editing remains essential not because it guarantees sales but because it prevents certain types of failure. Typos, grammatical errors, and structural problems generate negative reviews that damage discoverability. The investment in editing protects against downside risk even if it doesn’t create upside opportunity on its own.

What Actually Moves Books

Authors who consistently beat the 250-copy average typically share common characteristics that differentiate their approach from the majority.

They treat publishing as a business with strategic planning, investment, and long-term perspective. They write in series and finish what they start. They research their market before and during writing, not after. They invest appropriately in professional production—editing, covers, formatting. They build audience before needing that audience to buy. They launch deliberately with coordinated effort rather than simply uploading and hoping.

None of these elements is secret or inaccessible. The challenge isn’t knowing what works—it’s doing the work consistently over time.

The 250-copy average represents what happens when authors approach publishing casually or naively. It’s not a ceiling imposed from outside. It’s the natural result of underselling books that were under-prepared and under-supported into an oversaturated market that rewards deliberate effort and punishes its absence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does the 250-copy figure include free downloads and promotional giveaways?

Different surveys measure differently. Some include only paid sales while others count all distributed copies. The directional reality holds regardless: most self-published books reach very small audiences. Whether the precise number is 200, 250, or 300 matters less than understanding the underlying dynamic of market saturation and competition for attention.

How long does it typically take to know if a book will beat the average?

Initial launch performance provides early signals but isn’t determinative. Some books start slow and build through word-of-mouth. Others launch strong and fade quickly. The first 90 days offer reasonable indication of trajectory, but books with active marketing support can show meaningful sales years after publication. Declaring failure too early prevents potential late success.

Do traditionally published books face the same challenges?

Similar dynamics apply but with key differences. Traditional publishers provide production quality, distribution access, and some marketing support that most self-published books lack. However, traditional publishers also have limited attention—they focus resources on titles they expect to perform, leaving midlist and lower books undersupported. Plenty of traditionally published books sell fewer than 1,000 copies despite the publisher’s involvement.

Is there a minimum viable marketing budget for self-published books?

Minimums depend on genre, competition, and strategy. Some authors succeed with essentially zero paid marketing through organic platform building and reader communities. Others need thousands of dollars in advertising spend to gain traction. A reasonable starting expectation for advertising-dependent launches is $500 to $1,500 in the launch period, with ongoing spend proportional to return on investment.

How important are reviews for sales performance?

Reviews influence conversion rate (the percentage of browsers who become buyers) more than discovery. A book with fifty reviews converts browsers better than one with five reviews, all else equal. Reviews also provide social proof that reduces purchase hesitation. However, reviews don’t drive traffic—they help convert traffic that arrives through other means. Building review count matters but isn’t a substitute for visibility efforts.

Should authors avoid saturated genres entirely?

Not necessarily. Saturated genres are saturated because readers are abundant. The opportunity size compensates for the competition if you can differentiate effectively. Authors should avoid saturated genres if they have no unique angle, no willingness to invest seriously, and no tolerance for competitive pressure. Authors with compelling differentiation, adequate resources, and realistic expectations can succeed in competitive spaces.

What role does luck play in book sales success?

More than anyone wants to admit. Timing of cultural conversations, unexpected endorsements, algorithmic flukes, and countless other factors outside author control influence outcomes. The practical response is to make luck matter less through consistent effort across multiple titles. Each book is a chance for something to connect; authors who publish more quality books create more opportunities for fortune to favor them.