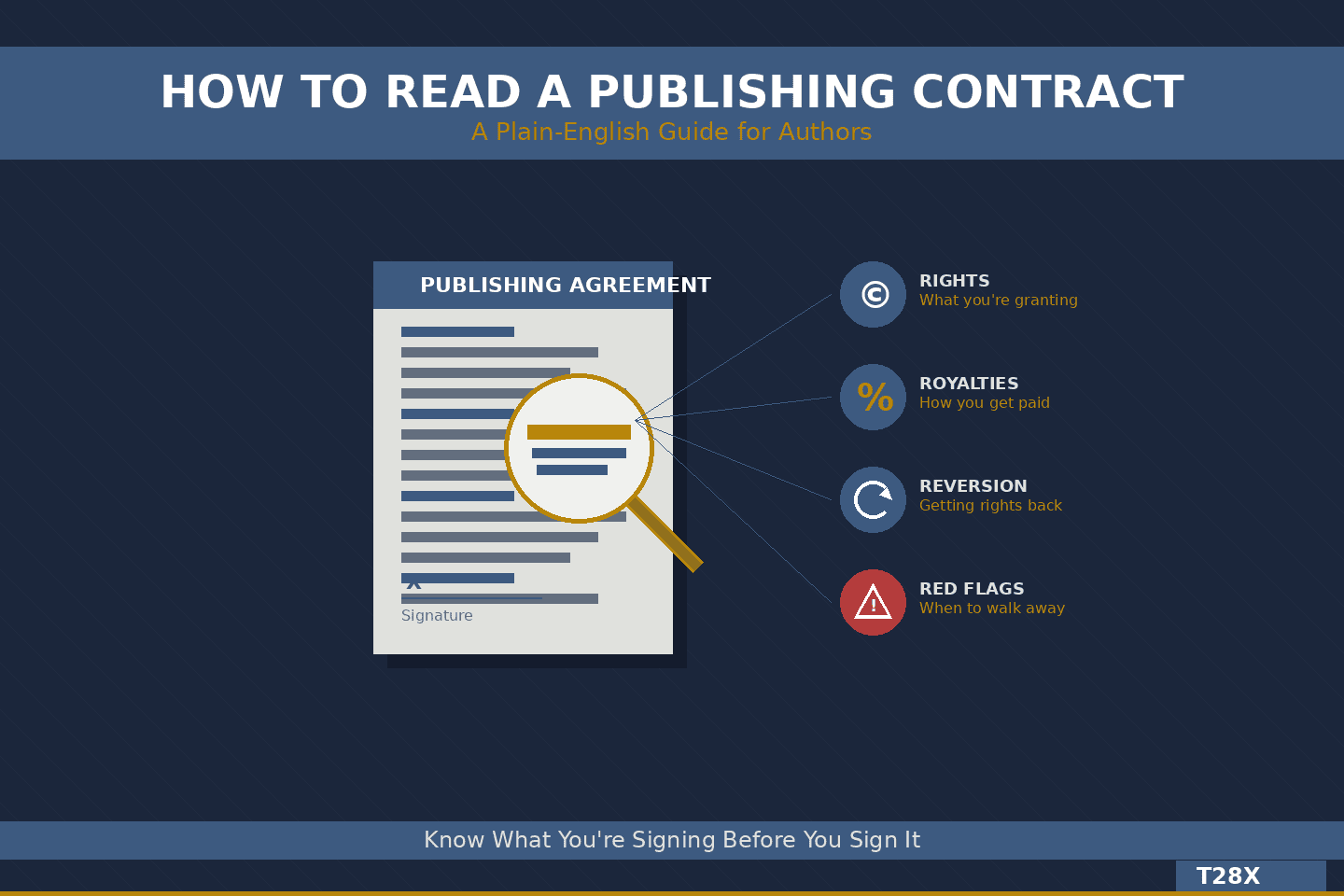

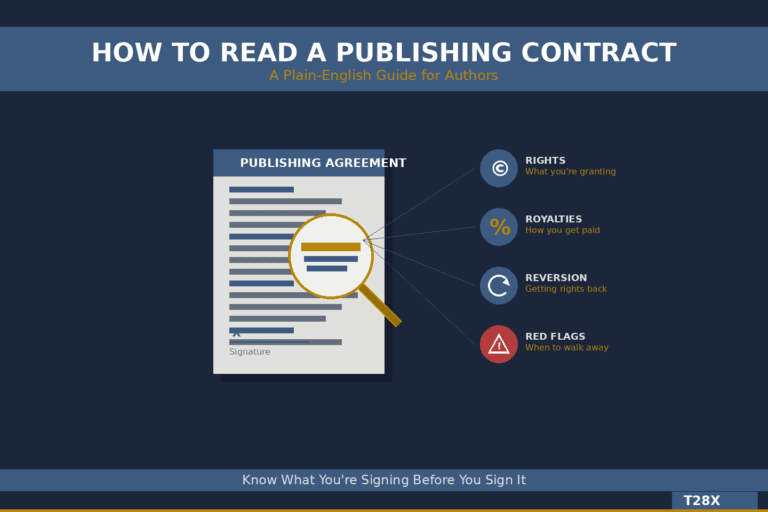

How to Read a Publishing Contract

Publishing contracts intimidate authors. The dense legal language, the unfamiliar terminology, the nagging fear that you’re signing away something important without realizing it. That fear is often justified.

We’ve reviewed contracts from traditional publishers, hybrid presses, and self-publishing services. The difference between a fair contract and a predatory one often hides in clauses that seem routine. This guide won’t replace legal counsel, but it will help you know which questions to ask and when to walk away.

The Grant of Rights: What You’re Actually Selling

Every publishing contract begins with a grant of rights. This clause determines what the publisher can do with your work and where they can do it.

Rights break down along several dimensions. Format rights specify whether the publisher controls print, ebook, audiobook, or all formats. Territory rights define geographic boundaries—North American rights differ from world English rights, which differ from world rights in all languages. Duration determines how long the publisher holds these rights.

A traditional publishing deal typically requests broad rights: all formats, world territory, for the life of copyright (your lifetime plus seventy years). This isn’t automatically predatory—major publishers need broad rights to justify their investment. But you should understand exactly what you’re granting.

The concerning pattern emerges with smaller publishers requesting major-publisher terms without offering major-publisher advances and distribution. If a press wants world rights in all formats for life of copyright, they should be paying accordingly and demonstrating the capacity to exploit those rights.

Subsidiary rights—film, television, merchandise, foreign translation—deserve particular attention. Many contracts bundle these with primary publishing rights. Some authors prefer retaining subsidiary rights or ensuring they receive the majority share of subsidiary income. The standard split varies, but authors typically receive 75 to 90 percent of subsidiary rights income, with the publisher taking a commission for facilitating deals.

Royalty Structures: Where the Money Lives

Royalty clauses determine your earnings from each sale. Understanding these numbers requires understanding what they’re calculated against.

Net royalties calculate against the publisher’s actual receipts after retailer and distributor discounts. A 25 percent net royalty on an ebook might yield $1.75 on a $9.99 book, since the publisher only receives about $7 after retailer cuts.

List price royalties (sometimes called cover price or retail royalties) calculate against the full sale price regardless of discounts. A 10 percent list price royalty on that same $9.99 ebook yields $1.00—less than the net calculation in this example.

Neither structure is inherently better. What matters is understanding which one you’re agreeing to and running the actual numbers. Publishers presenting net royalties as equivalent to list price royalties are being deliberately misleading.

Print royalties typically run 6 to 10 percent of list price for paperbacks, 10 to 15 percent for hardcovers. These numbers have remained relatively stable for decades. Ebook royalties vary more widely—traditional publishers often offer 25 percent of net, while some indie-friendly presses offer 40 to 50 percent of net.

Escalation clauses increase your royalty percentage after hitting sales thresholds. A contract might offer 8 percent on the first 10,000 copies, 10 percent on the next 10,000, and 12.5 percent thereafter. These clauses benefit authors of successful books and cost publishers nothing on books that underperform.

Watch for royalty reductions on special sales: deep discount sales, book club editions, premium and incentive sales, export sales. Standard language might cut your royalty by 50 percent or more on books sold at high discounts. This isn’t unreasonable—publishers genuinely earn less on these sales—but the specific thresholds matter. A publisher reducing royalties on any sale above 40 percent discount is being aggressive, since most trade sales involve discounts of 40 to 55 percent.

The Advance: More Than Just Money

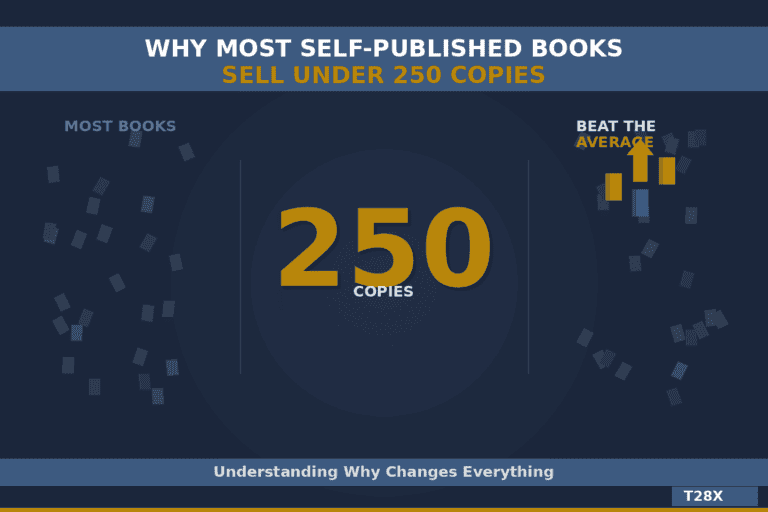

Advances represent the publisher’s financial commitment to your book. Beyond the obvious benefit of upfront payment, advances signal how hard a publisher will work to recoup their investment.

A $5,000 advance means the publisher needs to sell roughly 3,000 to 5,000 copies before your book earns additional royalties. They’re motivated to reach that threshold. A $500 advance or no advance at all means the publisher loses little if your book disappears.

Advance structures vary. Some publishers pay on signing. Others split payments across milestones: signing, delivery of final manuscript, and publication. Multi-book deals might spread advances across all contracted titles or pay separately for each.

“Earn-out” describes when your royalty earnings exceed your advance. Most books from traditional publishers never earn out, which sounds alarming until you realize that authors keep their advances regardless. An unearned advance isn’t a debt—it’s the publisher’s bet that didn’t pay off.

Joint accounting (also called cross-collateralization or basket accounting) allows publishers to apply earnings from one book against unearned advances on another. If your first book earns $3,000 in royalties but you received a $5,000 advance, and your second book earns $4,000 against a $5,000 advance, joint accounting means you’ve earned $7,000 against $10,000 in total advances—still $3,000 from earning out. Separate accounting would have your second book earning out and paying additional royalties while the first remains unearned. Authors generally prefer separate accounting.

Reversion Clauses: Getting Your Rights Back

Reversion clauses define how and when rights return to you if the publisher stops actively selling your book. This is arguably the most important protective language in any contract.

Traditional reversion triggers when a book goes “out of print.” The problem: print-on-demand technology means books technically never go out of print. A contract defining “in print” as “available for sale” grants effectively permanent rights regardless of actual sales activity.

Modern reversion language should include sales thresholds. If the book sells fewer than a specified number of copies (often 200 to 500) in a given period (typically twelve months), authors should have the right to request reversion. The specific numbers matter less than having numbers at all.

The reversion process also matters. Some contracts automatically revert rights when thresholds aren’t met. Others require the author to formally request reversion, giving the publisher time to remedy the situation. Some publishers can retain rights by demonstrating plans for new marketing or editions—language that can be abused to maintain control without actually investing.

Pay attention to what reverts. Some contracts revert primary rights but retain subsidiary rights already licensed. Others revert everything. The cleanest language returns all rights, with any existing subsidiary licenses continuing until their natural expiration.

Option Clauses: Controlling Your Future

Option clauses give publishers first look at your next work. Reasonable options protect publishers who invest in developing authors. Unreasonable options trap authors in relationships that no longer serve them.

A fair option clause gives the publisher exclusive first consideration of your next work in the same genre or series. It specifies a submission timeline (you must submit within a certain period after your current book publishes) and a response timeline (the publisher must decide within 30 to 90 days).

Problematic option clauses expand scope beyond reasonable boundaries. “Next work” language capturing any book you write in any genre grants far more control than justified. Options on multiple future works compound the problem. Options that match any competing offer rather than simply giving first refusal create negotiating nightmares.

The most dangerous option language ties terms to your existing contract. An option requiring your next book on “same terms” locks you into potentially outdated arrangements regardless of your growing market value or changing industry standards.

Authors with legitimate concerns about option clauses should negotiate before signing. Publishers usually accept reasonable limitations: same genre only, single book only, defined decision timelines, good faith negotiation on terms rather than matching existing contracts.

Non-Compete Clauses: What You Can’t Write

Non-compete clauses restrict your ability to publish other works that might compete with your contracted book. Some level of non-compete protection is reasonable—publishers shouldn’t have to compete against their own authors. But scope creep creates problems.

Reasonable non-compete language prevents you from publishing substantially similar works during the initial sales window of your book. A nonfiction author shouldn’t release a competing title on the same subject through another publisher while the first book is launching.

Problematic non-compete language extends too long (years instead of months), defines competition too broadly (anything in your genre rather than directly competing works), or restricts formats the publisher isn’t even using (preventing self-published ebooks when the publisher only has print rights).

The harshest non-competes effectively prevent prolific authors from maintaining reasonable output. An author contracted for one book per year who can’t publish anything else in their genre has essentially signed an exclusive employment agreement without employment benefits.

Red Flags That Should Stop Negotiations

Certain contract elements suggest fundamental problems with a publisher’s approach. These aren’t necessarily negotiating points—they’re signals to reconsider the relationship entirely.

Rights grabs exceeding the publisher’s capacity represent the clearest warning sign. A small press with no audiobook production capability demanding audio rights, or a domestic-only operation requiring world rights, suggests either inexperience or intentional overreach. Neither serves authors well.

Perpetual license language granting rights “for the full term of copyright” without meaningful reversion clauses should rarely be accepted outside major traditional deals. Your book should be able to come home if the publisher stops serving it.

Assignment clauses allowing the publisher to transfer your contract to any third party without your consent means you might end up published by a company you’ve never evaluated. Standard language requires author consent for assignment, sometimes with exceptions for corporate acquisitions or restructuring.

Warranty and indemnification clauses in all contracts require you to guarantee your work is original and non-infringing. Reasonable versions limit your liability to situations where you’ve actually done something wrong. Unreasonable versions make you liable for the publisher’s legal costs even in frivolous suits, or require you to indemnify against claims you had no way to prevent.

What Actually Deserves Legal Review

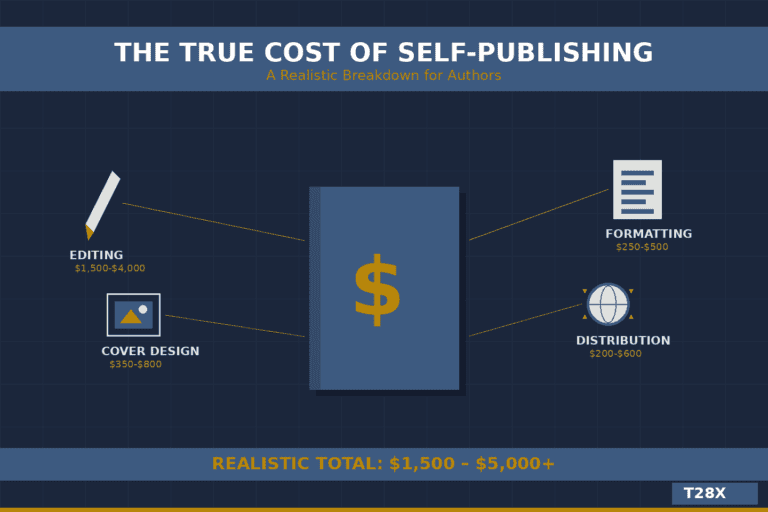

Not every contract requires an attorney. A straightforward self-publishing service agreement with limited rights transfer might be clear enough to evaluate yourself. But certain situations justify professional review.

Traditional publishing contracts almost always warrant attorney involvement. The complexity, duration, and financial stakes justify the cost. Publishing attorneys typically charge $300 to $600 for contract review—a worthwhile investment against decades-long agreements.

Any contract involving significant advances (generally over $5,000) deserves legal attention. The publisher has lawyers protecting their interests; you should have representation protecting yours.

Contracts from unfamiliar publishers benefit from legal review even at lower dollar amounts. Established publishers with standard contracts present known quantities. New or small operations might have unusual language that seems innocuous but creates problems.

The Authors Guild offers contract review services for members. Various professional organizations for genre writers provide similar resources. Literary attorneys specializing in publishing understand industry norms that generalist lawyers might miss.

Negotiation Reality

First-time authors have limited negotiating leverage with traditional publishers. This doesn’t mean accepting whatever’s offered, but it does mean picking battles strategically.

Focus negotiation on terms that matter most for your situation. An author planning a long series might prioritize favorable option terms. An author with film industry connections might fight hardest for subsidiary rights. An author concerned about publisher stability should emphasize reversion clauses.

Publishers expect negotiation on certain points and have pre-approved fallback positions. Advances often have flexibility. Certain subsidiary splits can be adjusted. Reversion thresholds might be negotiable. Other elements—base royalty rates, fundamental rights structure—rarely move for debut authors.

The negotiating dynamic shifts with subsequent books. Authors with track records have leverage. Authors whose first books exceeded expectations have significant leverage. Building that track record sometimes requires accepting imperfect first contracts, but never contracts that prevent you from building a career at all.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I negotiate a publishing contract without an agent?

Yes, though it’s harder. Agents know industry standards and have existing relationships with publishers. Unagented authors can still negotiate, but they should extensively research comparable deals and consider hiring a publishing attorney for the negotiation itself, not just contract review. Some publishers are more flexible with unagented authors; others view lack of representation as a signal to offer less favorable terms.

What happens if a publisher goes bankrupt?

Publishing rights typically become assets in bankruptcy proceedings. Your contract might be assumed by whoever acquires the publisher’s catalog, sold to another party, or rejected entirely (which would return rights to you). Bankruptcy creates uncertainty regardless of contract language, but strong reversion clauses improve your position. Authors should monitor publisher financial health and consider this risk when evaluating smaller presses.

How do collaboration agreements differ from standard contracts?

Collaboration agreements must address additional concerns: how creative control is divided, how authorship credit appears, how income splits work, what happens if one collaborator can’t complete their portion, and who controls decision-making if collaborators disagree. These agreements should exist between collaborators before any publisher contract, not be created within the publishing contract itself.

Should I worry about contracts from self-publishing services?

Self-publishing service contracts deserve scrutiny but involve different concerns. You’re typically licensing platform access rather than granting publishing rights. Watch for exclusivity requirements, termination restrictions, pricing control limitations, and ongoing fees. The risk isn’t losing rights to your work—you usually retain those—but being locked into an unsatisfactory service relationship.

What’s the difference between an option and a right of first refusal?

An option typically requires you to offer your next work before shopping it elsewhere, with defined terms or good-faith negotiation. A right of first refusal allows the publisher to match any offer you receive from another publisher. Options are more common in traditional publishing. First refusals can create complications because other publishers may not want to negotiate seriously knowing their offer can simply be matched.

How do I handle a publisher asking me to sign quickly?

Pressure to sign quickly is a red flag. Legitimate publishers understand that contracts represent major decisions deserving careful review. A publisher unwilling to give you reasonable time (two to four weeks minimum) either has something to hide or doesn’t respect author interests. Express willingness to proceed promptly after proper review; if they won’t accommodate that, reconsider the relationship.

Are there standard contracts I can compare mine against?

The Authors Guild, Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, Romance Writers of America, and other professional organizations publish model contracts or contract guidance. These resources help identify terms that deviate from industry norms. Keep in mind that “standard” varies by publisher size and genre—what’s normal for Big Five literary fiction differs from small press romance.