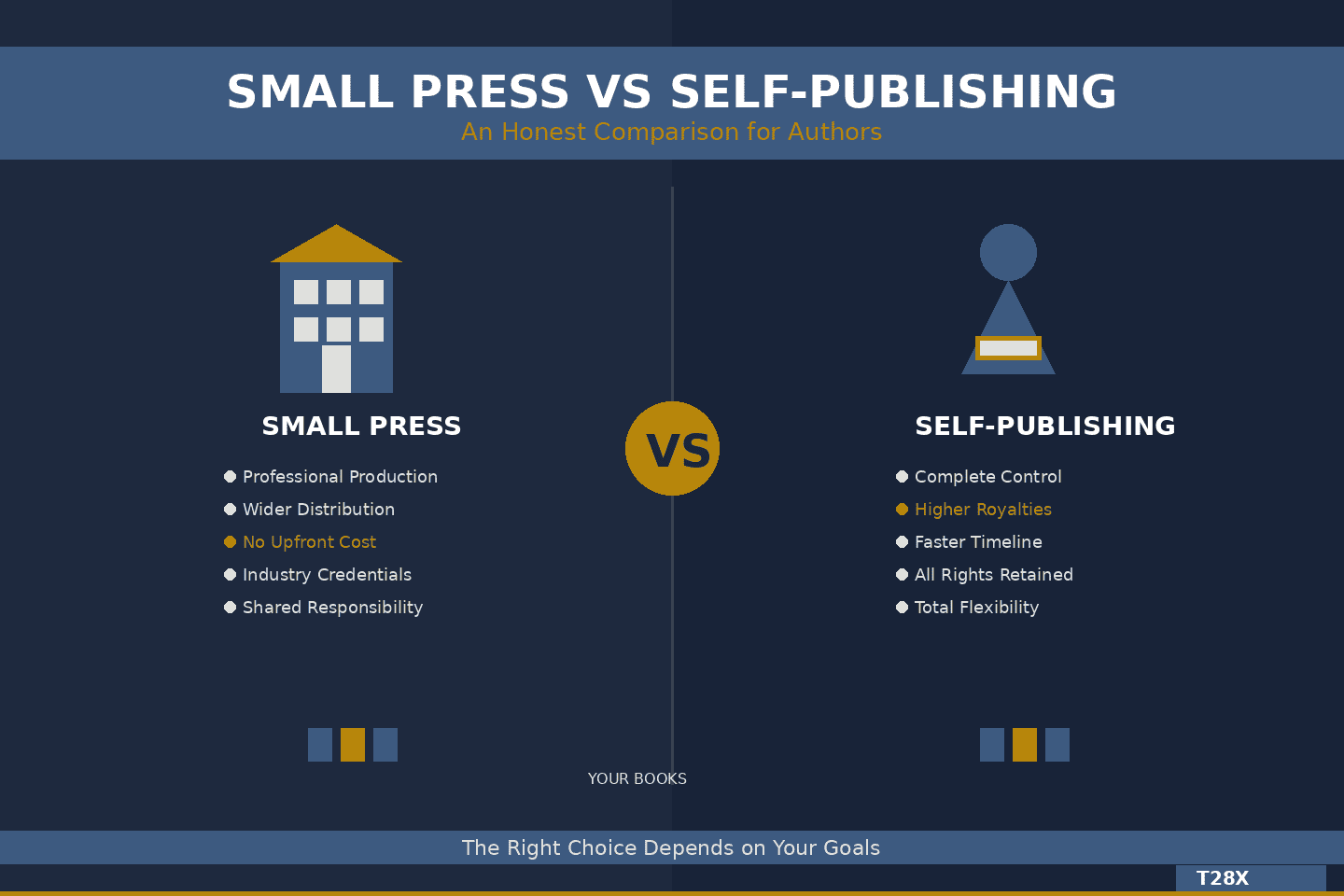

Small Press vs Self-Publishing: An Honest Comparison

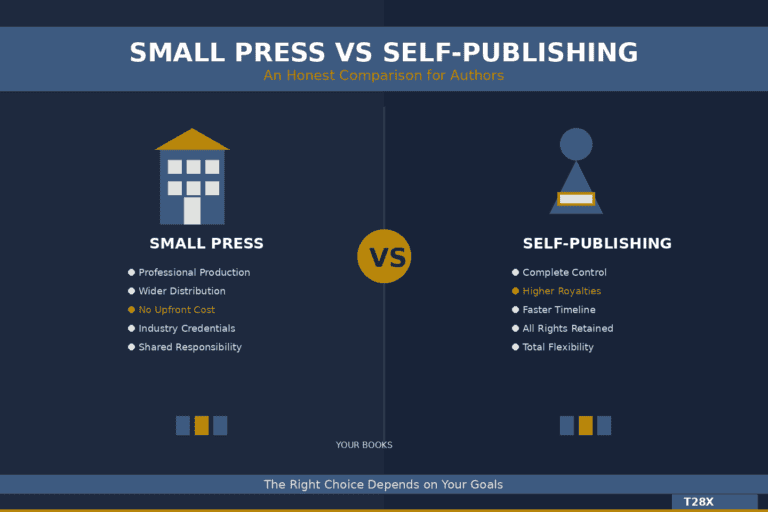

The decision between working with a small independent press and fully self-publishing isn’t as simple as most articles make it seem. Both paths have legitimate advantages. Both have real drawbacks. The right choice depends entirely on what you’re trying to achieve and what you’re willing to do yourself.

This comparison aims for honesty over advocacy. We’ll examine what small presses actually provide, what self-publishing actually requires, and help you determine which path fits your specific situation. There’s no universally correct answer—only the answer that’s correct for you.

Defining the Terms

Small presses (also called independent presses or indie publishers) are traditional publishers operating at smaller scale than major houses. They typically publish fewer titles annually, focus on specific genres or niches, and offer more personalized author relationships than big publishers. Some small presses are highly selective; others accept a broader range of work.

Self-publishing means you act as your own publisher. You control every decision, hire your own contractors, manage your own distribution, and retain all rights. The spectrum ranges from uploading a manuscript directly to Amazon to running a sophisticated publishing operation with professional teams.

Hybrid publishers occupy middle ground but aren’t covered here. True hybrid publishing involves cost-sharing between author and publisher, which creates different economics than either traditional small press or pure self-publishing models.

Creative Control: The Foundational Tradeoff

Self-publishing offers complete creative control. Every cover design decision, every editorial choice, every marketing direction—all yours. This appeals to authors with strong visions and clear market understanding.

Small presses involve collaborative control. Good small presses value author input and generally seek agreement on major decisions. But the publisher brings expertise and preferences that influence outcomes. Cover designs might not match your personal vision. Editorial feedback might push the book in directions you didn’t anticipate.

The question isn’t which approach is better but which you actually want. Authors who struggle with decisions often appreciate having publishing professionals guide the process. Authors with specific requirements often find collaboration frustrating even when the publisher’s instincts are sound.

Complete control also means complete responsibility. Self-published authors who choose wrong covers or skip editing own those consequences directly. Small press authors whose covers underperform can at least share the blame—cold comfort, but psychologically real.

Production Quality and Professional Support

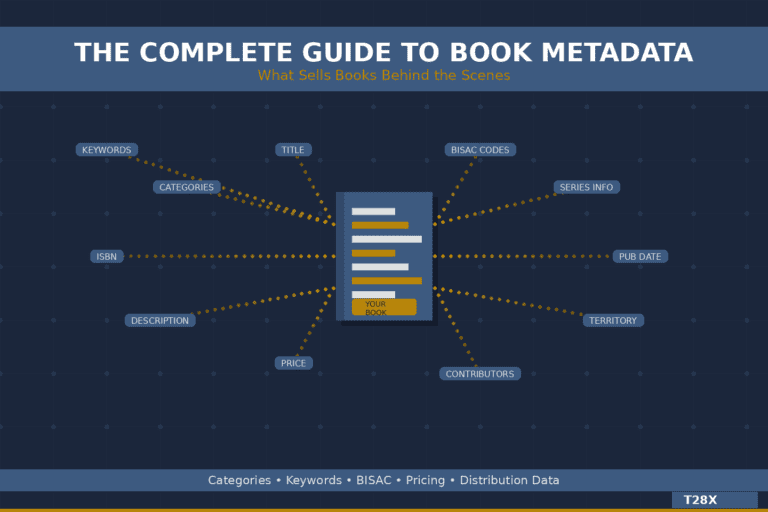

Small presses handle production professionally by definition. Editing, cover design, formatting, and metadata all fall to the publisher. The quality depends on the specific press—some maintain Big Five standards while others cut corners—but the author doesn’t manage these processes directly.

Self-publishing quality depends entirely on what you arrange and pay for. Authors who invest appropriately and choose good contractors achieve professional results. Authors who cut corners or choose poorly get subprofessional results. The range is enormous because no minimum standard exists.

The expertise gap matters beyond obvious quality markers. Small press publishers understand market positioning, category selection, pricing strategy, and launch timing from accumulated experience. First-time self-publishers learn these lessons through trial and error. The tuition for self-taught publishing education is paid in underperforming books.

Some self-published authors eventually develop genuine publishing expertise. After several releases, they understand their market as well as any small press. The question is whether you want to publish while learning or after learning—and whether you’re willing to have your early books serve as the learning vehicle.

Financial Reality

Self-publishing requires upfront investment with uncertain return. Professional editing, cover design, and formatting cost $1,500 to $5,000 for most books. Marketing adds more. These costs exist whether the book sells one copy or one hundred thousand.

Legitimate small presses don’t charge authors. Production costs come from the publisher’s investment, recovered through the publisher’s share of sales revenue. Authors avoid upfront financial risk but accept lower per-unit earnings.

The royalty comparison isn’t straightforward. Self-published ebooks through Amazon KDP yield roughly 70 percent of list price. Small press ebook royalties might be 25 to 50 percent of net receipts—a lower percentage of a differently calculated base. Print margins differ again.

Raw percentages favor self-publishing. But percentages of what? A self-published book selling 500 copies at $4.99 with 70 percent royalty yields roughly $1,750. A small press book selling 2,000 copies at $4.99 with 30 percent net royalty might yield roughly $2,000. If the press’s distribution and marketing actually drive higher sales, the lower percentage produces higher total income.

The relevant question isn’t which model pays better in abstract but which model will sell more of your specific book. For authors with existing platforms and marketing savvy, self-publishing typically wins financially. For authors relying on publisher distribution and support, small press economics often pencil out better despite lower percentages.

Distribution and Market Access

Amazon dominates self-publishing distribution. Self-published authors can also access other retailers through aggregators like Draft2Digital, but the practical reality is that most self-published sales happen on Amazon. Library and bookstore distribution remains challenging without a traditional publishing footprint.

Small presses typically distribute through industry-standard channels. IngramSpark or Ingram proper provides access to bookstores, libraries, and other retailers that rarely stock self-published titles. This access doesn’t guarantee orders, but it makes orders possible—a prerequisite the self-publishing path doesn’t easily satisfy.

The bookstore question particularly matters for certain genres and author goals. Literary fiction, poetry, regional interest, and children’s books benefit significantly from brick-and-mortar presence. Genre fiction readers increasingly shop online regardless of publisher, diminishing the bookstore advantage for those categories.

Library acquisition follows similar patterns. Librarians often purchase from familiar small press imprints while treating self-published books with skepticism. Authors prioritizing library penetration face meaningful barriers in pure self-publishing that small press affiliation reduces.

Time and Bandwidth Requirements

Self-publishing demands significant time investment. Beyond writing, authors must research contractors, brief designers, review edits, manage timelines, handle uploads, monitor sales, adjust strategy, and execute marketing. The total hours rival a part-time job during production and launch periods.

Small press authors focus primarily on writing and agreed promotional activities. The publisher handles production coordination, distribution management, and market positioning. This division frees creative bandwidth for the next book—which, for professional authors, often matters more than any single title.

The time tradeoff interacts with opportunity cost. Authors who can earn more money writing additional books than handling publishing logistics benefit from delegating those logistics. Authors whose writing time isn’t income-generating anyway might prefer controlling their publishing themselves.

Career stage affects this calculation. Early-career authors learning their craft might benefit from understanding every aspect of publishing even at slower pace. Established authors with backlists and reader expectations benefit from efficient production pipelines that keep books flowing steadily.

Marketing and Promotion Reality

Neither small presses nor self-publishing reliably include significant marketing. This disappoints authors who expect publishers to handle promotion, but the reality is that most books—regardless of publishing path—receive minimal marketing investment beyond what authors provide themselves.

Small presses typically offer more marketing support than self-publishing (which offers none by default) but less than authors imagine. A small press might handle metadata optimization, secure some review coverage, include books in catalog materials, and occasionally coordinate promotional pricing. Don’t expect advertising budgets, publicity tours, or dedicated marketing staff attention.

Self-published authors control their marketing completely but fund it completely as well. This enables aggressive advertising strategies impossible under traditional publishing constraints. Authors willing to invest in advertising and learn performance marketing often find self-publishing more conducive to direct marketing success.

The marketing reality argues for author involvement regardless of path. Authors who expect to simply write while others sell face disappointment under both models. Authors prepared to actively promote their work can do so effectively under either model, with different constraints and opportunities in each.

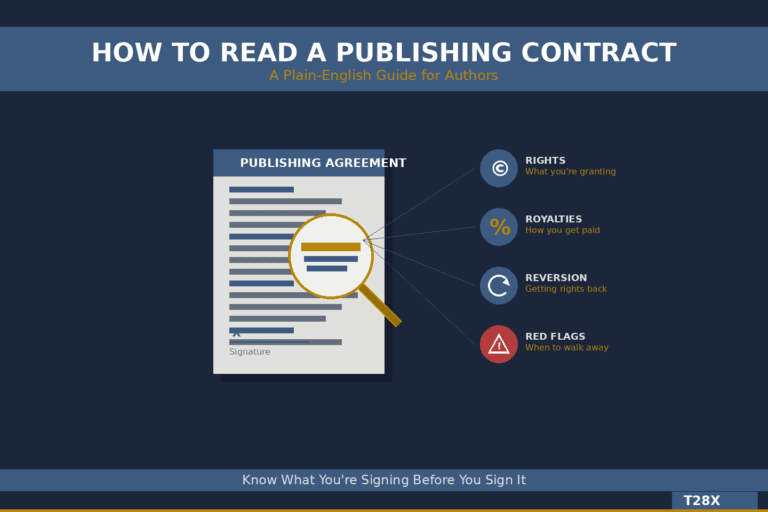

Rights and Long-Term Flexibility

Self-publishing preserves all rights permanently. Authors can change prices, update content, withdraw books, or pursue any opportunity without consulting anyone. This flexibility has real value over publishing careers measured in decades.

Small press contracts vary enormously in rights treatment. Some publishers request limited terms and narrow rights; others want everything forever. The specific contract matters more than generalizations about small presses as a category. Always evaluate actual contract language, not assumptions about what a “good” small press should offer.

Reversion—getting rights back from a publisher—represents the key flexibility question. Strong reversion clauses allow authors to recover rights if the publisher stops actively selling their book. Weak or absent reversion clauses can trap books in publishing limbo indefinitely. This concern applies to all traditional publishing relationships, not just small presses.

Successful books create the most problematic rights situations. A book earning significant royalties stays with its publisher whether or not the author wishes to move on. Self-publishing avoids this specific trap, though it creates others—like being permanently responsible for a book’s ongoing success.

Legitimacy and Professional Perception

Publishing industry attitudes toward self-publishing have evolved but remain complicated. Literary awards often exclude self-published titles. Major review outlets like Kirkus Reviews charge self-published authors for coverage that traditional books receive free. Some agents and publishers still view self-publishing backgrounds skeptically.

Small press affiliation provides traditional publishing credentials regardless of press size. A novel published by even a small independent press is traditionally published, which opens doors that self-publishing might not. This matters most for authors seeking hybrid careers—some self-published, some traditionally published—where credentialing affects opportunity access.

Reader perception has shifted dramatically. Most readers neither notice nor care about publisher identity. Self-published books with professional production quality are indistinguishable from traditionally published books to average buyers. The legitimacy question affects industry relationships more than reader relationships.

The question is whether industry legitimacy matters for your specific goals. Authors pursuing purely commercial self-publishing may never interact with traditional publishing infrastructure. Authors seeking traditional publishing deals, award consideration, or media coverage face different calculation.

Making the Decision

No single factor determines the right choice. Authors should weigh creative control preference, available investment capital, time bandwidth, marketing willingness, distribution priorities, and career goals together.

Self-publishing likely fits better if you value complete creative control unconditionally, have capital to invest in professional production, can dedicate time to learning and managing the publishing process, are willing to actively market your books, primarily target Amazon’s ebook market, and aren’t concerned with traditional publishing credentials.

Small press publishing likely fits better if you prefer collaborative creative process with professional input, lack capital for professional self-publishing investment, want to focus time on writing rather than publishing management, need access to bookstores and libraries, value traditional publishing credentials, and prefer sharing risk and responsibility with a publishing partner.

Many successful authors work both paths for different projects. Self-publishing enables rapid release schedules and maximum control for certain work. Small press relationships provide professional support and wider distribution for other work. The paths aren’t mutually exclusive over a career.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I find reputable small presses accepting submissions?

Research publishers of books similar to yours. Check acknowledgments in comparable titles for editor and agent names. Professional organizations like the Independent Book Publishers Association maintain member directories. Duotrope and Submission Grinder track submission opportunities. Always research any press before submitting—look for established track records, books actually in market, and reasonable contract terms.

If I self-publish first, can I later get a small press deal?

Yes, though with caveats. Publishers generally won’t republish existing self-published titles unless they’ve performed exceptionally. However, successful self-publishing demonstrates market viability and author platform—factors that help secure traditional deals for future books. Some authors leverage self-publishing success into traditional contracts for sequels or new series.

What sales level makes self-publishing definitely better financially?

There’s no universal threshold because publisher royalty structures vary too much. Generally, self-publishing becomes financially superior once you can reliably match or exceed the sales a small press would achieve. For most debut authors without existing platforms, small press distribution advantages often outweigh royalty differences. As platform develops and marketing skills grow, the calculation shifts.

Do small presses provide advances like traditional publishers?

Some do, most don’t. Small press advances, when offered, are typically modest—often $500 to $2,500 rather than the five-figure advances from larger houses. The absence of advances isn’t automatically a red flag for small presses, given their economic constraints. However, any press demanding payment from authors is not a legitimate traditional publisher regardless of what they call themselves.

How can I tell if a small press is legitimate before submitting?

Check for books actually published and available through major retailers. Search for author testimonials and experiences—not on the publisher’s own site but in writing communities. Verify they don’t charge authors (a critical distinction from vanity presses). Review sample contracts if available. A legitimate small press has visible, verifiable publishing activity and industry presence.

Can I self-publish and work with a small press simultaneously?

Generally yes, though some small press contracts include exclusivity clauses or right-of-first-refusal terms for future work. Many authors maintain separate self-published series alongside small-press-published work. Different pen names sometimes help keep publishing identities distinct. Always disclose existing self-publishing activity to potential publishers and review contracts for conflicts.

What’s the biggest mistake authors make choosing between these paths?

Underestimating self-publishing’s operational demands while overestimating small press marketing support. Authors who choose self-publishing expecting it to be easier than traditional routes face harsh reality. Authors who choose small presses expecting hands-off success face equal disappointment. Both paths require author involvement; they differ in where that involvement focuses.